Weekends

May is the month of long weekends, what the French call ponts. Frequently there are at least two ponts ("bridges") during May, thanks to two national holidays: May 1st and May 8th. A pont can last either three or four days.

If Labor Day (May 1st) falls on a Monday or Friday, there's a simple three-day weekend: shops and factories close up tight on the holiday itself. If it's a four-day weekend, with the holiday falling on a Tuesday or Thursday, workers and employees arrange for an extra day off so as to take advantage of the pont. If the holiday falls on a Saturday or Sunday, there is no pont.

Nowadays the May 1st holiday in France is a far cry from what it used to be in the 1960s and 1970s, when hundreds of thousands of people turned out for the labor demonstrations. Depending on the trade union one felt close to, one would go over to the Place de la République, the Place de la Bastille or the Place de la Nation in Paris, wave flags and banners, sing and chant lustily, and spend a fine day out with one's fellow unionists-cum-protestors. In recent years, these Labor Day events have become less and less frequented, partly because there are fewer union members and, in Amerloque's view, partly because of the disappearance of the USSR as a role model acting as a sort of counterweight to the capitalist model.

If May 1st is a pont, the national holiday VE Day (commemorating the Allied victory in World War II), which falls exactly one week later on May 8th, is similarly a pont. Needless to say, these two long weekends in a row can put severe strains on the French economy. In some mission-critical and public service sectors, such as steelmaking, energy production and hospitals, scheduling of personnel and planning begin months in advance so as to ensure as little disruption as possible.

Millions of people travel on the long spring weekends, by car, by train and plane. In many parts of France, these ponts are considered to be the opening days of the tourist season. Parisians and other city dwellers migrate briefly to the Riviera and to the Basque coastal beaches. Quite a few French families have résidences secondaires (vacation homes) and take advantage of the May weekends to open them up and air them out, in preparation for the summer, in-season residency.

To the delight of everyone – with the exception of businesses which have to juggle even more with personnel and production schedules ! – there is sometimes a third pont in May: l'Ascension. According to the Roman Catholic ecclesiastical calendar, on which some French national holidays are based, Ascension always falls on the Thursday of the sixth week after Easter. So May, 2006 has a third pont: three long weekends in one month, which contribute significantly to the quality of life in France !

For some French men and women, the month of May can be quite hectic. May heralds the runup to the baccalauréat, the matriculation exam at the conclusion of French secondary education. Successfully passing the bac guarantees admission to University, and students taking the bac put May to good use to review the subjects. The media devote quite a few reports to the bac, including interviews of instructors who try to predict which questions might be asked, especially in the philosophy portion.

May is also a time to finalize summer vacation plans, since each French worker is guaranteed five weeks of paid vacation per year. Not so long ago, most French people took their holidays during the month of August; Paris used to be almost completely shut down, much to the vast regret of tourists. In recent years, however, more and more people have been splitting their vacation time, using three or four weeks in the summer and allocating the remaining week(s) to a serious Christmas break or to a skiing jaunt in February. Nowadays a tendency is developing to take one's summer holiday between two national holidays: July 14th, Bastille Day, and August 15, l'Assomption. Vacation planning is a serious subject, here, and May weekends can be put to good use to coordinate with family members.

May is a month to relax and recharge one's batteries, too. Motoring from Paris out to his place in Normandy is an activity that Amerloque appreciates very, very much, and he indulges himself over the long weekends in May. Years ago he purchased a Norman farm with its main house built of colombage, the traditional wood-framed construction , and has been improving it little by little since then.

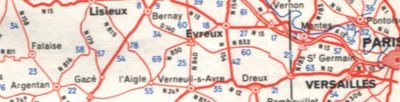

In the 1970s, going out to the farm was indeed an adventure: packing up everything, loading the car, and leaving Paris to the west, on the Nationale 12. Driving through Dreux, then switching onto the Nationale 26 at Verneuil-sur-Avre, motoring through L'Aigle and thence rolling through the wonderful studfarm country on the road signposted "Argentan" (Amerloque's place is northeast of Argentan, far off the main road and well hidden from prying eyes !). Given the state of the highways, cars and traffic – the road passed right through the sometimes congested town centers; tractors, cattle haulers and combine harvesters shared the roads with passenger vehicles - the trip took a bit over five hours, one way. A round-trip in one day was utterly unthinkable.

Frequently Amerloque would halt along the way in a bustling town or village to do the food shopping. There was a plethora of shops in each place, and Amerloque appreciated the diversity, the quality and the cost – it was quite a bit cheaper than in Paris. One could taste before purchasing and pick up excellent sausage, cheese, bread, fruit and wine for very little. The roadside family picnics in Normandy were imperatives: one took one's time, and life was the better for it.

In the 1980s, with the advent of the hypermarkets, the local shops slowly began disappearing. It became much harder and increasingly frustrating to assemble the ingredients for a Normandy picnic: the boulanger (baker) in town A had closed down, while the prizewinning boucherie / charcuterie (butcher / deli) in village B had morphed into a rudimentary convenience store, and the fromager (cheesemonger) in town C had, alas, simply disappeared. One could witness a whole way of life dying before one's eyes: townspeople were abandoning their usual shops, run by their friends and neighbors, to spend their money en masse at the soulless hypermarkets in the nearest large town. Consumerism – or, at least, a nascent French iteration of it - was on the march.

The 1990s saw months and years of roadworks along Amerloque's route. More and more people owned and used cars; far more goods were being transported by truck; traffic and time spent behind the wheel had become burning issues in the media and the popular mind. The central roadplanning authorities decided that the best way to proceed was double-barreled: a) widening the major highways to at least two lanes each way, while b) building new roads which went around the towns and villages, instead of through them. Enlarging the roads passing through the town centers would have been well-nigh impossible in any event, since some of the villages and towns were hundreds of years old, with historical buildings that could not be disfigured or demolished.

Some traffic jams and holdups due to construction and ancillary events are particularly memorable, including having neatly avoided a massive delay on the way back to Paris one sunny weekday afternoon in May, thanks to Mrs A's quick thinking. On the Nationale 26, just outside Verneuil, in front of the prestigious Ecole des Roches, gendarmes were handing out a traffic survey, with questions such as "How much time do you need to drive to work?". The gendarmes waited for the driver to fill in the questionnaire and hand it back. Having already been subjected to the same survey not a month previously, and seeing the line of vehicles, Mrs A jumped behind the wheel. She drove - on the wrong side of the road - to the front of the line of waiting cars and slid open the driver's window (the vehicle was a flaming red 1968 Mark II Morris Mini 'Parisienne') . To the surprised gendarme she sweetly said, in a low voice so that other drivers would not hear: Je ne crois pas que ce soit obligatoire et nous avons déjà effectué votre sondage … j'ai deux enfants en bas age qui m'attendent à Paris. Pouvons-nous poursuivre notre chemin, s'il vous plait ? ("I don't think this is mandatory and we've done your survey already … I have two very young children in Paris waiting for me. May we go on through, please ?" The gendarme smiled, answered Mais, bien sûr, Madame ! Bonne route ! ("Of course, Madam ! Have a nice journey !") and waved Mrs A through without further ado. Amerloque and Mrs A laughed all the way to Paris, since neither of them had any doubt whatsoever that the winning ingredient in Mrs A's argument was the mention of "very young children". The kids were not "very young" at all, by a long shot.

Amerloque finally decided, in the 1990s, to stop relying on local Norman products for picnics and schedule his trips so that that lunching and dining in restaurants would be possible, opening times outside of Paris being somewhat more restricted. Discovering new restaurants is always pleasureful in France: one rarely fares badly, and Amerloque was rarely disappointed. With the overall improvement in roads, travel times had been cut dramatically, so it was becoming quite practicable to make the return trip in the same day. Five hours, one-way, had been transformed into six hours, round trip. Speed and convenience had, in many ways, become paramount.

One of Amerloque's favorite restaurants was Chez Marinette, an establishment where traveling salesmen, families, and truckers shared tables and where traditional French cuisine was served. The parking lot was filled with sleek upmarket German vehicles, middle-class Peugeots and Renaults, as well as long distance trucks driven by routiers (truckdrivers) from France and, very rarely, from Europe. Marinette – for there was indeed a living, breathing Marinette – ran her place like the commander of a taut ship. Her food and beverages - including the carafed table wines, on which she prided herself - were always excellent – and at an affordable, reasonable price. Her version of tripes à la mode de Caen (Tripe, Caen style) was particularly successful.

By the beginning of the millennium, in the year 2000, the French had discovered roundabouts, aka "traffic circles" in some parts of the world. The roadworks along Amerloque's route to Normandy (portions of which were taken by American and French troops in 1944, by the way) continued apace: perfectly good intersections managed by traffic lights were savagely torn up, as were the surrounding stands of beautiful mature trees. Roundabouts were built, ostensibly to improve road safety and "improve the traffic pattern"; young saplings were planted. Simultaneously the remaining one-lane sections were, in the vast majority of cases, converted into two-lane express highways, incorporating passing lanes designed to allow passenger cars to overtake heavy trucks, of which an increasing number were from European countries.

Generally, in 2006, one must leave the main road to reach the center of town, after passing through quite a bit of ugly, hypermarket-driven, urban sprawl. Having himself upgraded to a sleek German road vehicle, Amerloque now manages to make the door-to-door round trip to his farm and back in about five hours, depending on the weather and time of day. Given the modernized roads and the scarcity of food shops in the towns, Amerloque sees no reason at all to stop, since he visited their tourist attractions, such as they are, long ago. Mondialisation oblige, there are more and more trucks, most of them from foreign countries, on the improved roadways.

"Et chez Marinette ?", the attentive reader might ask. "Amerloque still dines there, right ?"

Not really. Chez Marinette is gone. Since last year the building has housed a Chinese restaurant, with gaudy, mawkish exterior decor. Every time Amerloque passes by at lunchtime – and Amerloque is quite sure it is open for lunch – he observes that the parking lot contains hardly any vehicles: a couple of passenger cars at most, and no trucks. In the evening the restaurant is lit up, but, again, the parking lot is virtually empty. The traditional Chez Marinette is yet another sacrifice on the altar of globalization, and Normandy is the poorer for it.

L'Amerloque

Text © Copyright 2006 by L'Amerloque

If Labor Day (May 1st) falls on a Monday or Friday, there's a simple three-day weekend: shops and factories close up tight on the holiday itself. If it's a four-day weekend, with the holiday falling on a Tuesday or Thursday, workers and employees arrange for an extra day off so as to take advantage of the pont. If the holiday falls on a Saturday or Sunday, there is no pont.

Nowadays the May 1st holiday in France is a far cry from what it used to be in the 1960s and 1970s, when hundreds of thousands of people turned out for the labor demonstrations. Depending on the trade union one felt close to, one would go over to the Place de la République, the Place de la Bastille or the Place de la Nation in Paris, wave flags and banners, sing and chant lustily, and spend a fine day out with one's fellow unionists-cum-protestors. In recent years, these Labor Day events have become less and less frequented, partly because there are fewer union members and, in Amerloque's view, partly because of the disappearance of the USSR as a role model acting as a sort of counterweight to the capitalist model.

If May 1st is a pont, the national holiday VE Day (commemorating the Allied victory in World War II), which falls exactly one week later on May 8th, is similarly a pont. Needless to say, these two long weekends in a row can put severe strains on the French economy. In some mission-critical and public service sectors, such as steelmaking, energy production and hospitals, scheduling of personnel and planning begin months in advance so as to ensure as little disruption as possible.

Millions of people travel on the long spring weekends, by car, by train and plane. In many parts of France, these ponts are considered to be the opening days of the tourist season. Parisians and other city dwellers migrate briefly to the Riviera and to the Basque coastal beaches. Quite a few French families have résidences secondaires (vacation homes) and take advantage of the May weekends to open them up and air them out, in preparation for the summer, in-season residency.

To the delight of everyone – with the exception of businesses which have to juggle even more with personnel and production schedules ! – there is sometimes a third pont in May: l'Ascension. According to the Roman Catholic ecclesiastical calendar, on which some French national holidays are based, Ascension always falls on the Thursday of the sixth week after Easter. So May, 2006 has a third pont: three long weekends in one month, which contribute significantly to the quality of life in France !

For some French men and women, the month of May can be quite hectic. May heralds the runup to the baccalauréat, the matriculation exam at the conclusion of French secondary education. Successfully passing the bac guarantees admission to University, and students taking the bac put May to good use to review the subjects. The media devote quite a few reports to the bac, including interviews of instructors who try to predict which questions might be asked, especially in the philosophy portion.

May is also a time to finalize summer vacation plans, since each French worker is guaranteed five weeks of paid vacation per year. Not so long ago, most French people took their holidays during the month of August; Paris used to be almost completely shut down, much to the vast regret of tourists. In recent years, however, more and more people have been splitting their vacation time, using three or four weeks in the summer and allocating the remaining week(s) to a serious Christmas break or to a skiing jaunt in February. Nowadays a tendency is developing to take one's summer holiday between two national holidays: July 14th, Bastille Day, and August 15, l'Assomption. Vacation planning is a serious subject, here, and May weekends can be put to good use to coordinate with family members.

May is a month to relax and recharge one's batteries, too. Motoring from Paris out to his place in Normandy is an activity that Amerloque appreciates very, very much, and he indulges himself over the long weekends in May. Years ago he purchased a Norman farm with its main house built of colombage, the traditional wood-framed construction , and has been improving it little by little since then.

In the 1970s, going out to the farm was indeed an adventure: packing up everything, loading the car, and leaving Paris to the west, on the Nationale 12. Driving through Dreux, then switching onto the Nationale 26 at Verneuil-sur-Avre, motoring through L'Aigle and thence rolling through the wonderful studfarm country on the road signposted "Argentan" (Amerloque's place is northeast of Argentan, far off the main road and well hidden from prying eyes !). Given the state of the highways, cars and traffic – the road passed right through the sometimes congested town centers; tractors, cattle haulers and combine harvesters shared the roads with passenger vehicles - the trip took a bit over five hours, one way. A round-trip in one day was utterly unthinkable.

Frequently Amerloque would halt along the way in a bustling town or village to do the food shopping. There was a plethora of shops in each place, and Amerloque appreciated the diversity, the quality and the cost – it was quite a bit cheaper than in Paris. One could taste before purchasing and pick up excellent sausage, cheese, bread, fruit and wine for very little. The roadside family picnics in Normandy were imperatives: one took one's time, and life was the better for it.

In the 1980s, with the advent of the hypermarkets, the local shops slowly began disappearing. It became much harder and increasingly frustrating to assemble the ingredients for a Normandy picnic: the boulanger (baker) in town A had closed down, while the prizewinning boucherie / charcuterie (butcher / deli) in village B had morphed into a rudimentary convenience store, and the fromager (cheesemonger) in town C had, alas, simply disappeared. One could witness a whole way of life dying before one's eyes: townspeople were abandoning their usual shops, run by their friends and neighbors, to spend their money en masse at the soulless hypermarkets in the nearest large town. Consumerism – or, at least, a nascent French iteration of it - was on the march.

The 1990s saw months and years of roadworks along Amerloque's route. More and more people owned and used cars; far more goods were being transported by truck; traffic and time spent behind the wheel had become burning issues in the media and the popular mind. The central roadplanning authorities decided that the best way to proceed was double-barreled: a) widening the major highways to at least two lanes each way, while b) building new roads which went around the towns and villages, instead of through them. Enlarging the roads passing through the town centers would have been well-nigh impossible in any event, since some of the villages and towns were hundreds of years old, with historical buildings that could not be disfigured or demolished.

Some traffic jams and holdups due to construction and ancillary events are particularly memorable, including having neatly avoided a massive delay on the way back to Paris one sunny weekday afternoon in May, thanks to Mrs A's quick thinking. On the Nationale 26, just outside Verneuil, in front of the prestigious Ecole des Roches, gendarmes were handing out a traffic survey, with questions such as "How much time do you need to drive to work?". The gendarmes waited for the driver to fill in the questionnaire and hand it back. Having already been subjected to the same survey not a month previously, and seeing the line of vehicles, Mrs A jumped behind the wheel. She drove - on the wrong side of the road - to the front of the line of waiting cars and slid open the driver's window (the vehicle was a flaming red 1968 Mark II Morris Mini 'Parisienne') . To the surprised gendarme she sweetly said, in a low voice so that other drivers would not hear: Je ne crois pas que ce soit obligatoire et nous avons déjà effectué votre sondage … j'ai deux enfants en bas age qui m'attendent à Paris. Pouvons-nous poursuivre notre chemin, s'il vous plait ? ("I don't think this is mandatory and we've done your survey already … I have two very young children in Paris waiting for me. May we go on through, please ?" The gendarme smiled, answered Mais, bien sûr, Madame ! Bonne route ! ("Of course, Madam ! Have a nice journey !") and waved Mrs A through without further ado. Amerloque and Mrs A laughed all the way to Paris, since neither of them had any doubt whatsoever that the winning ingredient in Mrs A's argument was the mention of "very young children". The kids were not "very young" at all, by a long shot.

Amerloque finally decided, in the 1990s, to stop relying on local Norman products for picnics and schedule his trips so that that lunching and dining in restaurants would be possible, opening times outside of Paris being somewhat more restricted. Discovering new restaurants is always pleasureful in France: one rarely fares badly, and Amerloque was rarely disappointed. With the overall improvement in roads, travel times had been cut dramatically, so it was becoming quite practicable to make the return trip in the same day. Five hours, one-way, had been transformed into six hours, round trip. Speed and convenience had, in many ways, become paramount.

One of Amerloque's favorite restaurants was Chez Marinette, an establishment where traveling salesmen, families, and truckers shared tables and where traditional French cuisine was served. The parking lot was filled with sleek upmarket German vehicles, middle-class Peugeots and Renaults, as well as long distance trucks driven by routiers (truckdrivers) from France and, very rarely, from Europe. Marinette – for there was indeed a living, breathing Marinette – ran her place like the commander of a taut ship. Her food and beverages - including the carafed table wines, on which she prided herself - were always excellent – and at an affordable, reasonable price. Her version of tripes à la mode de Caen (Tripe, Caen style) was particularly successful.

By the beginning of the millennium, in the year 2000, the French had discovered roundabouts, aka "traffic circles" in some parts of the world. The roadworks along Amerloque's route to Normandy (portions of which were taken by American and French troops in 1944, by the way) continued apace: perfectly good intersections managed by traffic lights were savagely torn up, as were the surrounding stands of beautiful mature trees. Roundabouts were built, ostensibly to improve road safety and "improve the traffic pattern"; young saplings were planted. Simultaneously the remaining one-lane sections were, in the vast majority of cases, converted into two-lane express highways, incorporating passing lanes designed to allow passenger cars to overtake heavy trucks, of which an increasing number were from European countries.

Generally, in 2006, one must leave the main road to reach the center of town, after passing through quite a bit of ugly, hypermarket-driven, urban sprawl. Having himself upgraded to a sleek German road vehicle, Amerloque now manages to make the door-to-door round trip to his farm and back in about five hours, depending on the weather and time of day. Given the modernized roads and the scarcity of food shops in the towns, Amerloque sees no reason at all to stop, since he visited their tourist attractions, such as they are, long ago. Mondialisation oblige, there are more and more trucks, most of them from foreign countries, on the improved roadways.

"Et chez Marinette ?", the attentive reader might ask. "Amerloque still dines there, right ?"

Not really. Chez Marinette is gone. Since last year the building has housed a Chinese restaurant, with gaudy, mawkish exterior decor. Every time Amerloque passes by at lunchtime – and Amerloque is quite sure it is open for lunch – he observes that the parking lot contains hardly any vehicles: a couple of passenger cars at most, and no trucks. In the evening the restaurant is lit up, but, again, the parking lot is virtually empty. The traditional Chez Marinette is yet another sacrifice on the altar of globalization, and Normandy is the poorer for it.

L'Amerloque