Chips

Easter Monday in France is a national holiday.

Nominally a secular country, France still celebrates some public holidays which are based on days of religious significance. Way back when, when the vast majority of the French were practicing Catholics, the lundi de Pâques holiday was necessary so that people could recover from eating and digesting the tremendous meals served on Easter Sunday. According to church doctrine, Easter is the culmination of Lent, a 40-day season which, many years ago, included rigorous fasting. So after the privations of Lent – and the serious celebrations during Holy Week, especially on Good Friday – believers pulled out all the stops on Easter Sunday to break the fast. Monday was – and is - the day to recover.

France has many conventions linked to food: lamb is habitually on the menu at Easter, although beef has been gaining ground in recent times, since there are fewer practicing Catholics. Amerloque follows the French tradition and every year a gigot d'agneau graces the family table, served with flageolets (white beans), onions and potatoes. The lamb is preceded by crudités, while cheese and fresh fruit in season round out the meal. Not too much, not too heavy – just enough for a holiday Sunday, while not enough to require rest and digestion on the Monday following.

Wine is an important part of any French celebratory meal, of course. Amerloque is wondering, though, just how long it will be before moderately-expensive traditional French wine will become more difficult to obtain. "Whatever are you talking about ?" the attentive reader might ask. "France is justly renowned for its wines ! C'est une spécificité française !"

For several years now, the wine industry in France, which accounts for over 75,000 full time jobs, has been in crisis. There are basically two reasons for this.

The first and major reason is simply the fact that less wine is being consumed by French people. Dining habits are changing: in 1975 a meal in France lasted 1h38m, but nowadays (2005) a repas only takes 0h31m. The public authorities have cracked down on drunk driving: what was a acceptable alcohol intake several years ago is no longer allowed on the road: the police have been issuing tickets like there's no tomorrow. Wine has been replaced by other beverages, such as water and juices. To cut a long story short wine consumption in France dropped by 57% between 1961 and 2003.

The second explanation is that French wines at export have run into serious competition from wines of the "New World": South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and Chile, for example. These "innovative" wines have made serious inroads into markets that the French winemakers, who ensure approximately one-fifth of the world's production, once considered their own. The French vignerons and chateaux are hurting, badly.

Devised and refined over decades and decades, the French concept of the terroir is the basis for classifying and ranking wines. Terroir refers to the combination of natural factors associated with a particular vineyard: soil, underlying rock, altitude, terrain, orientation toward the sun, microclimate … there are many parameters. Each French vineyard is unique and the system is complex, with its numerous and somewhat arcane appellations. The consumer must be educated, which takes time, effort and money: it is not a trivial task.

Winemakers in the "New World" countries usually label their wines by the grapes used to make them -- such as Cabernet Sauvignon or Pinot Noir -- and often add a description of the wines' qualities. Terroir counts for nothing.

Manufacturing processes are quite different, too. French wines ("Great wines are made in the vineyard", the saying goes) are aged in expensive oaken barrels, while the simple addition of wood chips to enhance taste is fully permitted in New World wines. Needless to say, it costs far less to drop a few bags or bundles of oak chips into a stainless steel vat than it does to make wine carefully in the traditional barrel. As a matter of fact, with the former method, the taste can be programmed. Little education of the consumer is required.

Last autumn an accord was reached between the USA and the European Union. One part of the agreement was that the Bush administration would put a bill before Congress to restrict the use of European wine place names: for example, Burgundy, Claret, Haut-Sauterne, Hock, Madeira, Malaga, Marsala, Moselle, Port, Rhine, Sauterne, Sherry and Tokay. A second portion of the agreement dealt with wine-making techniques and certification issues. The European Union said it would accepts some U.S. wine-making practices, such as special filtration methods and adding wood chips during the aging process to produce an oak flavor, practices that are totally or partially banned in the EU. Once again, France was stabbed in the back by the European Union when it signed on for wood chips.

Several years ago, because they didn't consider the international competition a threat, the French winemakers' associations and the French government were loath to spend the money required to educate consumers outside of France about French wines. When they did allot a bit of cash, it was too little, and usually in the wrong places They finally awoke to the enormity of the challenge … far, far too late, alas.

The incidents concerning the First Job Contract (CPA) have monopolized the news in France for almost two months, but a couple of weeks ago, a report ordered by the Ministry of Agriculture and signed by one Bernard Pomel was revealed. The title is "Making A Successful Future For French Winemaking" (Réussir l'avenir de la viticulture française). The report speaks of "making wine for consumers" and "going against French taste", according to commentaries in Le Figaro.

The crux of the report ? The author states that wood chips must be added to wine, so as to "seduce foreign palates" (séduire les palais étrangers). He continues "We have to adapt to globalization. We must produce wines for consumers, and not the wines that winemakers dream of". (Il faut s'adapter à la mondialisation. Il faut faire le vin du consommateur et non pas le vin dont le producteur rêve.)

For the moment, there has been relatively little public discussion about this. Amerloque has seen several articles in the press in which some winemakers say "wood chips are a good idea" and others say "never, over my dead body", but there seems to be far too much silence. Amerloque hopes that consumers will wake up to this threat to tradition and quality. Certainly if someone like José Bové takes up the torch, there will inevitably be more discussion.

Wood chips in French wines ? Instead of fighting the competition from a recognized position of strength and pouring money into educating the consumer and selling France, those is charge at the Ministry of Agriculture prefer to play catch-up ball and go with the bottomfeeding flow. Why give up yet another characteristic that contributes to the French way of life ? The decisionmakers have decided to join those who are unraveling and destroying France, little by little, in order to "save" it. They don't even see that in fifteen or twenty years, the "New World" wines, in order to differentiate among themselves and gain a competitive advantage over one another, will be putting emphasis on their individual "terroir", on their climate, lands and vineyards. The wheel will have come full circle; it always does.

* * * * *

How will the consumers know that a wine was manufactured traditionally rather than artificially flavored with oak chips ?

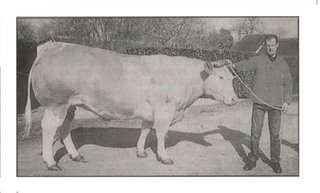

French consumers out in Normandy around Eastertide every year need ask no questions about the quality of the beef on their tables. Here's a typical ad in a regional newspaper this week.

"On the occasion of the Easter holidays, your master butcher has selected a hybrid Maine-Anjou Charolaise heifer, (awarded the Grand Prix d'Honneur at agricultural fairs in Mortrée, in Mortagne-au-Perche, and in Mamers), from Monsieur Portmann, (breeder) in Neaufles-Avergny."

Sic transit gloria mundi.

L'Amerloque

Nominally a secular country, France still celebrates some public holidays which are based on days of religious significance. Way back when, when the vast majority of the French were practicing Catholics, the lundi de Pâques holiday was necessary so that people could recover from eating and digesting the tremendous meals served on Easter Sunday. According to church doctrine, Easter is the culmination of Lent, a 40-day season which, many years ago, included rigorous fasting. So after the privations of Lent – and the serious celebrations during Holy Week, especially on Good Friday – believers pulled out all the stops on Easter Sunday to break the fast. Monday was – and is - the day to recover.

France has many conventions linked to food: lamb is habitually on the menu at Easter, although beef has been gaining ground in recent times, since there are fewer practicing Catholics. Amerloque follows the French tradition and every year a gigot d'agneau graces the family table, served with flageolets (white beans), onions and potatoes. The lamb is preceded by crudités, while cheese and fresh fruit in season round out the meal. Not too much, not too heavy – just enough for a holiday Sunday, while not enough to require rest and digestion on the Monday following.

Wine is an important part of any French celebratory meal, of course. Amerloque is wondering, though, just how long it will be before moderately-expensive traditional French wine will become more difficult to obtain. "Whatever are you talking about ?" the attentive reader might ask. "France is justly renowned for its wines ! C'est une spécificité française !"

For several years now, the wine industry in France, which accounts for over 75,000 full time jobs, has been in crisis. There are basically two reasons for this.

The first and major reason is simply the fact that less wine is being consumed by French people. Dining habits are changing: in 1975 a meal in France lasted 1h38m, but nowadays (2005) a repas only takes 0h31m. The public authorities have cracked down on drunk driving: what was a acceptable alcohol intake several years ago is no longer allowed on the road: the police have been issuing tickets like there's no tomorrow. Wine has been replaced by other beverages, such as water and juices. To cut a long story short wine consumption in France dropped by 57% between 1961 and 2003.

The second explanation is that French wines at export have run into serious competition from wines of the "New World": South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and Chile, for example. These "innovative" wines have made serious inroads into markets that the French winemakers, who ensure approximately one-fifth of the world's production, once considered their own. The French vignerons and chateaux are hurting, badly.

Devised and refined over decades and decades, the French concept of the terroir is the basis for classifying and ranking wines. Terroir refers to the combination of natural factors associated with a particular vineyard: soil, underlying rock, altitude, terrain, orientation toward the sun, microclimate … there are many parameters. Each French vineyard is unique and the system is complex, with its numerous and somewhat arcane appellations. The consumer must be educated, which takes time, effort and money: it is not a trivial task.

Winemakers in the "New World" countries usually label their wines by the grapes used to make them -- such as Cabernet Sauvignon or Pinot Noir -- and often add a description of the wines' qualities. Terroir counts for nothing.

Manufacturing processes are quite different, too. French wines ("Great wines are made in the vineyard", the saying goes) are aged in expensive oaken barrels, while the simple addition of wood chips to enhance taste is fully permitted in New World wines. Needless to say, it costs far less to drop a few bags or bundles of oak chips into a stainless steel vat than it does to make wine carefully in the traditional barrel. As a matter of fact, with the former method, the taste can be programmed. Little education of the consumer is required.

Last autumn an accord was reached between the USA and the European Union. One part of the agreement was that the Bush administration would put a bill before Congress to restrict the use of European wine place names: for example, Burgundy, Claret, Haut-Sauterne, Hock, Madeira, Malaga, Marsala, Moselle, Port, Rhine, Sauterne, Sherry and Tokay. A second portion of the agreement dealt with wine-making techniques and certification issues. The European Union said it would accepts some U.S. wine-making practices, such as special filtration methods and adding wood chips during the aging process to produce an oak flavor, practices that are totally or partially banned in the EU. Once again, France was stabbed in the back by the European Union when it signed on for wood chips.

Several years ago, because they didn't consider the international competition a threat, the French winemakers' associations and the French government were loath to spend the money required to educate consumers outside of France about French wines. When they did allot a bit of cash, it was too little, and usually in the wrong places They finally awoke to the enormity of the challenge … far, far too late, alas.

The incidents concerning the First Job Contract (CPA) have monopolized the news in France for almost two months, but a couple of weeks ago, a report ordered by the Ministry of Agriculture and signed by one Bernard Pomel was revealed. The title is "Making A Successful Future For French Winemaking" (Réussir l'avenir de la viticulture française). The report speaks of "making wine for consumers" and "going against French taste", according to commentaries in Le Figaro.

The crux of the report ? The author states that wood chips must be added to wine, so as to "seduce foreign palates" (séduire les palais étrangers). He continues "We have to adapt to globalization. We must produce wines for consumers, and not the wines that winemakers dream of". (Il faut s'adapter à la mondialisation. Il faut faire le vin du consommateur et non pas le vin dont le producteur rêve.)

For the moment, there has been relatively little public discussion about this. Amerloque has seen several articles in the press in which some winemakers say "wood chips are a good idea" and others say "never, over my dead body", but there seems to be far too much silence. Amerloque hopes that consumers will wake up to this threat to tradition and quality. Certainly if someone like José Bové takes up the torch, there will inevitably be more discussion.

Wood chips in French wines ? Instead of fighting the competition from a recognized position of strength and pouring money into educating the consumer and selling France, those is charge at the Ministry of Agriculture prefer to play catch-up ball and go with the bottomfeeding flow. Why give up yet another characteristic that contributes to the French way of life ? The decisionmakers have decided to join those who are unraveling and destroying France, little by little, in order to "save" it. They don't even see that in fifteen or twenty years, the "New World" wines, in order to differentiate among themselves and gain a competitive advantage over one another, will be putting emphasis on their individual "terroir", on their climate, lands and vineyards. The wheel will have come full circle; it always does.

* * * * *

How will the consumers know that a wine was manufactured traditionally rather than artificially flavored with oak chips ?

French consumers out in Normandy around Eastertide every year need ask no questions about the quality of the beef on their tables. Here's a typical ad in a regional newspaper this week.

"On the occasion of the Easter holidays, your master butcher has selected a hybrid Maine-Anjou Charolaise heifer, (awarded the Grand Prix d'Honneur at agricultural fairs in Mortrée, in Mortagne-au-Perche, and in Mamers), from Monsieur Portmann, (breeder) in Neaufles-Avergny."

Sic transit gloria mundi.

L'Amerloque