Speed

France is quite rightly considered to be the home of food, fashion, culture and savoir vivre, but it is also a place where technological know-how is present in daily life. Transport is a case in point.

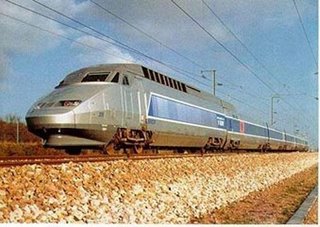

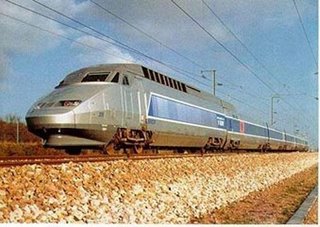

Recently the country celebrated the twenty-fifth birthday of the TGV: the high speed train (train à grande vitesse) that revolutionized train travel in France. Hitting an average top speed of some 250 kilometers per hour on certain routes, the TGV, in its various forms, has carried substantially over one billion passengers. One can now travel from Paris to Lyons, a distance of 463 km (287 miles), in just under two hours. By car, the same trip takes about four and a half hours, if the weather and traffic are favorable. By train from Paris to Avignon is now only two and a half hours … while on the roads it takes about six hours, forty minutes, if the gods of motoring look favorably on one's efforts. Marseilles – on the Mediterranean, mare nostrum ! – is only three hours away from the capital. Still, the flight time to Marseilles is about one hour twenty minutes, to which have to be added the airport commute time and possible delays at the airport, of course.

Certainly the TGV is a technological marvel and can be very well suited to one's lifestyle in France. It is great for singles, bobos, and suffering commuters. For example: Amerloque knows white-collar breadwinners who commute from Lyons to their jobs in Paris two or three times per week, thus benefiting from the economic dynamics of Paris while taking advantage of the excellent quality of life in the French provinces.

There are some serious drawbacks to using the TGV, all the same. If one is a family man or woman, hauling kids and the needed accessories and required paraphernalia on the trains is always a hassle, and it's even more of one on the TGV, which is not particularly baggage- or child-friendly. The cost can be high, too. There are various reductions in ticket prices: special rates for large families, for example, or when traveling at "non-peak hours", but voyaging as a family is expensive on the "normal" trains - and even more expensive on the TGV. If one has a pet that one wants to take along, and a considerable amount of bulky luggage, the hassles on the TGV, where the luggage areas are rather small, are truly frustrating. Finally, one is dependent on some bureaucrat's idea of schedules, which tend markedly toward commuter convenience.

Amerloque has always found the food on the TGVs to be quite removed from the greatness of the technology. He has accompanied foreigners on the TGVs and each time, without fail, they have been surprised and bitterly disappointed by the "cuisine" served on board. One wonders what the SNCF is thinking: here is a showpiece of French technology being abysmally betrayed by poor customer service, hostile sandwiches and almost undrinkable coffee. France's well-deserved reputation for tremendous dining really takes a hit, on the TGV. Back in the good old days, when taking the train meant leisurely travel in some comfort, the dining cars and the cuisine on French trains were eagerly looked forward to – and remembered. Nowadays, efficiency rules.

On balance, travelling by TGV might be great for some people – singles and childless couples - while an automobile is better – and cheaper, even with the ownership and running costs factored in – for families.

One major result of the TGV has been a certain decentralization of French activity - but perhaps not of power, per se. In some respects, Paris is now less the center of the French universe, since people are able to move faster and more easily between their homes in the provinces and jobs in Paris. On the other hand, a Parisian executive now thinks very little of going to Lyons or Marseilles in the morning, meeting with employees during the day, and returning to Paris the very same evening. Though some top schools have moved from Paris to the provinces, to which teachers and students can commute more easily, decisions are still taken at the Ministry of Education in Paris. Central control, that dirigisme dear to the French, is reinforced.

In recent years more and more people – especially families – have fled Paris and established their residences eighty or one hundred kilometers away. Naturally property values have soared along the TGV routes, and dwellings such as the traditional mas in the south of France, which were eminently affordable a decade ago, are now priced astronomically. The demand from weekending Parisians has simply been added to the background, Europewide real estate speculation. In the property markets, location is everything, as always.

American and French expats sometimes debate the desirability of TGVs in the USA. Constructing a TGV (or a TGV-like web of trains: perhaps mag-lev) in the USA is a waste of money, in Amerloque's view. There are several reasons for this, he feels.

The first is, quite simply, scale. The country is far bigger than France. When it's 21h00 in San Francisco, it's midnight in Boston. Imagine what four hours of flight time (that is, LA to NY) means from Paris ! After all, when it's 21h00 in Paris, it's 23h00 in … Moscow, which is two hours away by air. What cities are four hours away by air from Paris ?

A second reason is the cost. Too expensive. Many Americans feels that there are far, far better things for governments to spend money on than a TGV or two. Tax money is precious and not infinitely extensible; one can attribute the horrible gaps in US public services – such as those in education, roads, and power infrastructures - to the American desire for "low taxes". In Amerloque's view, American governments would do better to increase spending on healthcare and education. Amerloque remembers seeing figures concerning the purchase of possible high speed train rights-of-way in Florida and Texas, and they were astronomical. With the recent Supreme Court decision about eminent domain, state legislatures are having to take a renewed look at where, when, and why the doctrine might be applied, and for whose benefit – and are passing some new laws.

The third and final reason is freedom. The insistence on the TGV in France (and train travel in general in Europe) is a reflection of just how "government" is perceived: as the fount from which all good things flow, as the cornucopia of plenty. In the USA, "government" is not perceived in the same fashion.

Perhaps one or two well-defined corridors might be good places to build a US TGV, because they could receive a mixture of public and private financing. Maybe Washington DC -> NY City, for example, or San Diego -> San Francisco -> Seattle, or even the much shorter Orlando -> Miami. However, putting a plethora of TGVs around the country would be an egregious waste of money. With greenhouse warming apparently threatening the planet, arguments for building one or more TGVs in the USA might appear attractive, on the surface. However, TGVs will undoubtedly not "reduce the number of cars", nor would they "cut pollution" since only a portion of those commuters already using cars in the given corridors would be potential TGV users.

A few years ago, just before the turn of the century, thestreet.com came up with a list of the top 100 US business events during the twentieth century. In first position ? "Eisenhower creates the interstates: June 29, 1956". The judges sum up their choice nicely:

Conceived by President Dwight D. Eisenhower as he rode over the German autobahns as supreme allied commander at the end of World War II, signed into law on June 29, 1956 and built over four decades at a cost of $130 billion, the interstates bind us together even as they free us to move and dream. The frontier hasn't closed; it runs everywhere now, on those quiet, essential lanes of blacktop.

The US has interstates, and France has the TGV - as well as number of autoroutes, which have been built at a furious pace over the last fifteen years or so.

Now that the infrastructures have been constructed, the next step in both countries is to produce vehicles which pollute far, far less, and which use alternative energy sources as much as possible. Quite a challenge: one which each country will rise to magnificently - in its own way, of course.

L'Amerloque

Text © Copyright 2006 by L'Amerloque

Recently the country celebrated the twenty-fifth birthday of the TGV: the high speed train (train à grande vitesse) that revolutionized train travel in France. Hitting an average top speed of some 250 kilometers per hour on certain routes, the TGV, in its various forms, has carried substantially over one billion passengers. One can now travel from Paris to Lyons, a distance of 463 km (287 miles), in just under two hours. By car, the same trip takes about four and a half hours, if the weather and traffic are favorable. By train from Paris to Avignon is now only two and a half hours … while on the roads it takes about six hours, forty minutes, if the gods of motoring look favorably on one's efforts. Marseilles – on the Mediterranean, mare nostrum ! – is only three hours away from the capital. Still, the flight time to Marseilles is about one hour twenty minutes, to which have to be added the airport commute time and possible delays at the airport, of course.

Certainly the TGV is a technological marvel and can be very well suited to one's lifestyle in France. It is great for singles, bobos, and suffering commuters. For example: Amerloque knows white-collar breadwinners who commute from Lyons to their jobs in Paris two or three times per week, thus benefiting from the economic dynamics of Paris while taking advantage of the excellent quality of life in the French provinces.

There are some serious drawbacks to using the TGV, all the same. If one is a family man or woman, hauling kids and the needed accessories and required paraphernalia on the trains is always a hassle, and it's even more of one on the TGV, which is not particularly baggage- or child-friendly. The cost can be high, too. There are various reductions in ticket prices: special rates for large families, for example, or when traveling at "non-peak hours", but voyaging as a family is expensive on the "normal" trains - and even more expensive on the TGV. If one has a pet that one wants to take along, and a considerable amount of bulky luggage, the hassles on the TGV, where the luggage areas are rather small, are truly frustrating. Finally, one is dependent on some bureaucrat's idea of schedules, which tend markedly toward commuter convenience.

Amerloque has always found the food on the TGVs to be quite removed from the greatness of the technology. He has accompanied foreigners on the TGVs and each time, without fail, they have been surprised and bitterly disappointed by the "cuisine" served on board. One wonders what the SNCF is thinking: here is a showpiece of French technology being abysmally betrayed by poor customer service, hostile sandwiches and almost undrinkable coffee. France's well-deserved reputation for tremendous dining really takes a hit, on the TGV. Back in the good old days, when taking the train meant leisurely travel in some comfort, the dining cars and the cuisine on French trains were eagerly looked forward to – and remembered. Nowadays, efficiency rules.

On balance, travelling by TGV might be great for some people – singles and childless couples - while an automobile is better – and cheaper, even with the ownership and running costs factored in – for families.

One major result of the TGV has been a certain decentralization of French activity - but perhaps not of power, per se. In some respects, Paris is now less the center of the French universe, since people are able to move faster and more easily between their homes in the provinces and jobs in Paris. On the other hand, a Parisian executive now thinks very little of going to Lyons or Marseilles in the morning, meeting with employees during the day, and returning to Paris the very same evening. Though some top schools have moved from Paris to the provinces, to which teachers and students can commute more easily, decisions are still taken at the Ministry of Education in Paris. Central control, that dirigisme dear to the French, is reinforced.

In recent years more and more people – especially families – have fled Paris and established their residences eighty or one hundred kilometers away. Naturally property values have soared along the TGV routes, and dwellings such as the traditional mas in the south of France, which were eminently affordable a decade ago, are now priced astronomically. The demand from weekending Parisians has simply been added to the background, Europewide real estate speculation. In the property markets, location is everything, as always.

American and French expats sometimes debate the desirability of TGVs in the USA. Constructing a TGV (or a TGV-like web of trains: perhaps mag-lev) in the USA is a waste of money, in Amerloque's view. There are several reasons for this, he feels.

The first is, quite simply, scale. The country is far bigger than France. When it's 21h00 in San Francisco, it's midnight in Boston. Imagine what four hours of flight time (that is, LA to NY) means from Paris ! After all, when it's 21h00 in Paris, it's 23h00 in … Moscow, which is two hours away by air. What cities are four hours away by air from Paris ?

A second reason is the cost. Too expensive. Many Americans feels that there are far, far better things for governments to spend money on than a TGV or two. Tax money is precious and not infinitely extensible; one can attribute the horrible gaps in US public services – such as those in education, roads, and power infrastructures - to the American desire for "low taxes". In Amerloque's view, American governments would do better to increase spending on healthcare and education. Amerloque remembers seeing figures concerning the purchase of possible high speed train rights-of-way in Florida and Texas, and they were astronomical. With the recent Supreme Court decision about eminent domain, state legislatures are having to take a renewed look at where, when, and why the doctrine might be applied, and for whose benefit – and are passing some new laws.

The third and final reason is freedom. The insistence on the TGV in France (and train travel in general in Europe) is a reflection of just how "government" is perceived: as the fount from which all good things flow, as the cornucopia of plenty. In the USA, "government" is not perceived in the same fashion.

Perhaps one or two well-defined corridors might be good places to build a US TGV, because they could receive a mixture of public and private financing. Maybe Washington DC -> NY City, for example, or San Diego -> San Francisco -> Seattle, or even the much shorter Orlando -> Miami. However, putting a plethora of TGVs around the country would be an egregious waste of money. With greenhouse warming apparently threatening the planet, arguments for building one or more TGVs in the USA might appear attractive, on the surface. However, TGVs will undoubtedly not "reduce the number of cars", nor would they "cut pollution" since only a portion of those commuters already using cars in the given corridors would be potential TGV users.

A few years ago, just before the turn of the century, thestreet.com came up with a list of the top 100 US business events during the twentieth century. In first position ? "Eisenhower creates the interstates: June 29, 1956". The judges sum up their choice nicely:

Conceived by President Dwight D. Eisenhower as he rode over the German autobahns as supreme allied commander at the end of World War II, signed into law on June 29, 1956 and built over four decades at a cost of $130 billion, the interstates bind us together even as they free us to move and dream. The frontier hasn't closed; it runs everywhere now, on those quiet, essential lanes of blacktop.

The US has interstates, and France has the TGV - as well as number of autoroutes, which have been built at a furious pace over the last fifteen years or so.

Now that the infrastructures have been constructed, the next step in both countries is to produce vehicles which pollute far, far less, and which use alternative energy sources as much as possible. Quite a challenge: one which each country will rise to magnificently - in its own way, of course.

L'Amerloque